Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio: a fellow

of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy: he hath

borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how

abhorred in my imagination it is!Toward the end of 1996 I was in my parents' living room reading a

Time magazine. It was one of those year-end wrap-up issues, with various lists and capsule reviews of the best books, films, art, and so on of the year soon to bow out. This was my senior year of high school. I had a girlfriend, or was moving toward having a girlfriend—My first "real" girlfriend. I was reading the magazine and in the books section, one book caught my eye: A book called

Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace. I don't remember why, but something in the capsule review sparked my interest. I had always been a reader, but this book—1,079 pages, about an "entertainment" called

Infinite Jest that is so pleasurable that those who saw it lost all desire to do anything but watch it, and thus died—seemed a whole other order of magnitude beyond what I'd been reading.

I bought the book. I think this was in December. I bought the book and started reading it. For the whole second half of my last year of high school, January through May or thereabouts, I read

Infinite Jest. I read it in class, and got in trouble for it. I gave it to my girlfriend, Shannon, for Valentine's Day, and she was touched because a boy had never given her a book before.

Infinite Jest was indeed about this entertainment, but it was about so much more. It was about addiction and a real American sort of sadness; it was about the future, and maybe where we were headed. It was also about two characters, Don Gately and Hal Incandenza—characters that are as alive to me as any other real living and breathing person. They live with me still today.

Infinite Jest turned me on to serious reading, and to the style of writing that I've come most to prefer: the sprawling, encyclopedic novel. David Foster Wallace turned me on to Pynchon, to Joyce, to Gaddis, to DeLillo. DFW—as he would come to be known to me—made me want to be a writer. But why?

For this reason:

Infinite Jest made me feel less alone. And DFW meant to do that. In an interview published in 1993 in

The Review of Contemporary Fiction, he said the following:

I had a teacher I liked who used to say good fiction's job was to comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable. I guess a big part of serious fiction's purpose is to give the reader, who like all of us is sort of marooned in her own skull, to give her imaginative access to other selves. Since an ineluctable part of being a human self is suffering, part of what we humans come to art for is an experience of suffering, necessarily a vicarious experience, more like a sort of generalization of suffering. Does this make sense? We all suffer alone in the real world; true empathy's impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with characters' pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside. It might be just that simple.

I was disturbed and

Infinite Jest comforted me. I was comfortable and

Infinite Jest disturbed me.

Infinite Jest made me feel less alone. And but so, ever since that late winter, spring, and early summer of 1997, I've been trying to write—and trying somehow, in my own small way, to follow in David Foster Wallace's footsteps: To make others, through writing, feel less alone. If I have ever written anything that anyone liked, that even for a moment made them feel unalone, then I have succeeded. And success is entirely relative; though I will in all probability never achieve near as much as DFW did, it doesn't matter—A drop of water is the ocean in miniature.

***

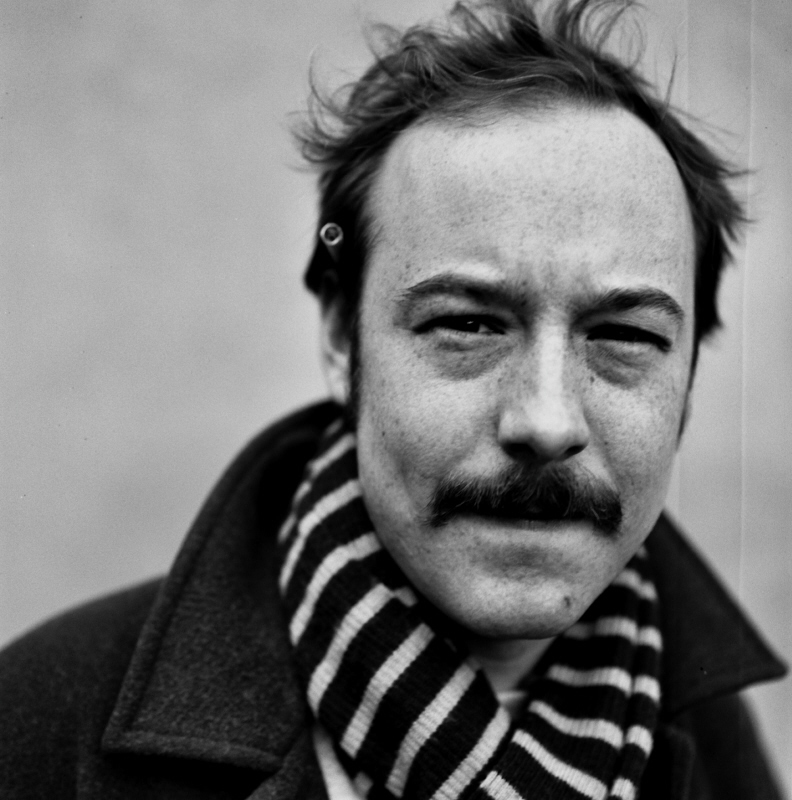

David Foster Wallace is dead. He hanged himself on Friday at his home in Claremont, Calif. He was 46.

***

I could go on. I could tell you about reading all his other books, from

Broom of the System (his first novel) to his most recent, a collection of essays called

Consider the Lobster; I could tell you about how I gave

Infinite Jest to a friend once, and how she later brought it back to me, signed; I could tell you how another girlfriend got another of his books,

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, signed by him for me, the summer she was in New York, and how she gave him a copy of our school's literary magazine, in which I had a couple of poems; I hoped that maybe he flipped through it on the plane ride back to the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, where he was teaching at the time, and read my poems and maybe liked them; I could tell you about how I very nearly went on a pilgrimage to see him in Illinois, but didn't, and how I wish now that I had.

I could tell you about how he was a laugh-out-loud funny writer—He had to have been to have worked into a 10,000-word review of a dictionary an analogy to a stoned person watching the PGA Tour with Oreo crumbs all over his shirt's front and being caught in a loop of thinking about what the color "green"

really means. I could tell you about all the times I've told friends,s significant others, and virtual strangers, "You have to read this book." Or I could tell you about how, in the special edition of

Rolling Stone published soon after 9/11, David Foster Wallace's take on that day's tragedy, called "The View from Mrs. Thompson's House" (since reprinted in

Consider the Lobster), was the most dead-on and honest assessment I've ever read about 9/11, in its throwing-up-the-hands-and-saying-I-just-don't-fucking-know-ness. I could tell you about how once I got to see him in New York, with Jonathen Franzen, as part of

The New Yorker Literary Festival, and how he blasted Franzen—no dope himself—entirely out of the water.

Or how now, reading

Infinite Jest for the third time around in 11 years, having gotten sober myself, in the last 100-page home stretch, this evening on the couch before a dinner party, and then the dinner party and outside, after, smoking a cigarette with some people, and a guy getting a text message and saying that David Foster Wallace had killed himself felt first like a friend had died, and then like a repudiation of something, a core-shaking of my own personal foundation—

But I'll not tell you about all that. I'll leave some things for memory and choose not to go down certain roads; I think DFW would want it that way. But, I will tell you this: David Foster Wallace's writing made me and millions of others feel less alone. I know that. And for this he should be praised, and mourned. I hope he has found the peace that eluded him in this life.

Rest in peace, DFW. I'll still be here, pushing your books on friends.